USAFE TAB-VEE shelters and their genesis

I've always been intrigued by the idea of building a 1/72 scale version of a USAFE TAB-VEE shelter, like I had seen at bases like Spangdahlem, Ramstein, Hahn and others. In 2020 I started looking for open sources on the subject, and found many documents with detailed information. They also tell how the US aircraft shelter evolved, and I found it fascinating. Hence this report starts in the early 1960s. Since these shelters are now 50 years old, and open to the public in many cases (think of Bitburg, Soesterberg, Hahn), I don't think they still are military secrets.

Wonder Building Corporation

The 'Wonder Building Corporation of America' was located in Chicago (IL). The company is sometimes called 'Wonder Trussless Building Cooperation' but I think the 'trussless' part comes from a logo used in advertisements. Wonder Building Corp produced a line of steel arch elements that were used to build roof structures, usually called a 'Wonder arch' or a 'Wonder roof'. They were used to build small factory halls, warehouses, swimming pool halls, aircraft hangars, etc. The archived Wonder buildings - assembly and specification manual from 1960 gives a great overview of the civilian applications of this type of structure. Unfortunately, the manual does not describe the arch elements themselves.

More specialized applications of 'Wonder arches' were found on the South Pole, see US Arctic Program Photo Library and Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Wonder Buildings also tapped into the private fallout shelter market. In 'Oppenheimer Is Watching Me: A Memoir', writer Jeff Porter states: "The Chicago Wonder Building Corporation was selling two hundred fallout shelters a week by 1961, at a thousand dollars a crack, and had become famous for their 'trussless' form (erect it yourself!)"

I think Wonder Building Corporation no longer exists, but I found a Spanish video of the Erection of a Wonder prefabricated steel building

Although the word is never used to describe the Wonder structures, they are true monocoques, because the 'skin' is the only structural member. I think the idea compares to the Nissen hut, although these had a wooden semi-circular frame (purlin) each 1.6 m, and are thus not true monocoque structures. Similarly, the 'Romney hut' and the 'Quonset hut' have frames / purlins too, and on the Quonson hut the corrugations are mostly horizontal, meaning it does not contribute to the strength and merely serves as covering.

One of modern equivalents of the Wonder Arch is the K-Span. The single-piece arches are made on site, starting with a roll of flat steel sheet. Here's a video of a K-Span in Afghanistan, and another in Czech Republic: Construction of production arched hall. Chinese versions can be seen too: K-Span forming machine and K-Span machine maxine [sic]. Another modern version of the Wonder Arch is Quick Span Arch Building Machine.

Aircraft shelters in Vietnam

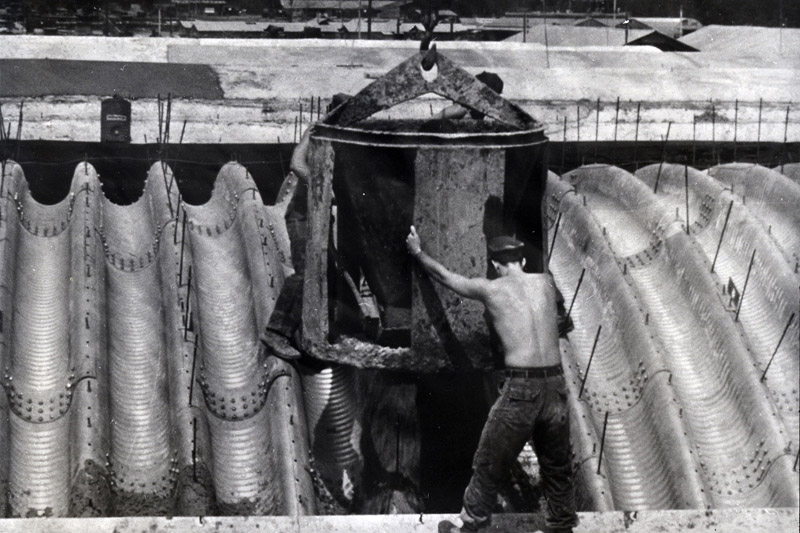

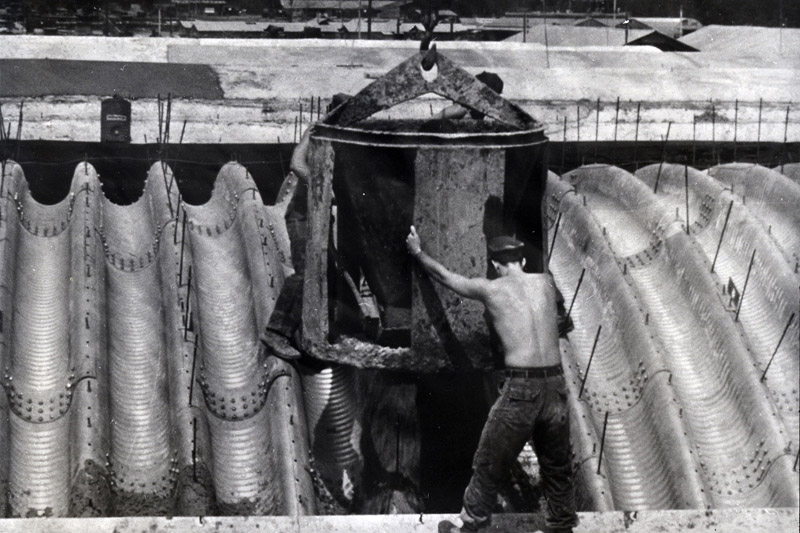

Starting in 1968, some 500 aircraft shelters were built in South-Vietnam, to protect the aircraft against ground attacks. These shelters had been developed since 1962 under 'Project 1597' ('Protective Shelters for Tactical Aircraft') and 'Project Concrete Sky', and used the Wonder arch structure as a main component. A number of articles and books contain solid information about these Vietnam shelters. But first a quick view in three pictures how the Vietnam shelters were built.

| Arch elements are bolted together. These elements were produced by US Steel (USS), whose logo is printed twice on each element. Element length varied per manufacturer. The bolting made construction a laborious process.

|

| A set of three half-rings is built up and then erected. I roughly calculate a weight of 5500 lbs / 2500 kg.

|

|

| With the wonder arch structure ready, concrete is poured in 4 feet heights. The top section is not poured inside a casing, but apparently shaped by hand. The rod ends that stick out are probably used to indicate the concrete layer thickness.

|

The book Southeast Asia: Building the Bases. The history of construction in Southeast Asia reports on pages 388-390 that:

An Air Force Weapons Laboratory Study concluded their first tests in May of 1965. At that time, AFWL had found one "off-the-shelf" bit of hardware which might work as the basis for further bomb shelter tests. This was the double-corrugated steel arch building made by the Wonder Trussless Building Company. AFWL did further testing with the Wonder Trussless steel arch, using various materials for covers—meaning impact protection and insulation on top of the steel, between 1966 and 1968. Tests were at Eglin, Kirtland and Hill Air Force Bases. The materials used for reinforcement against blast and penetration were earth, soil cement, sandbags, and concrete. The extra emergency of the Tet Offensives lent urgency to the needs — many aircraft were destroyed and damaged by enemy rockets, mortars and artillery in many types of revetments then in use in Vietnam. The AFWL conclusion was that an 18-inch cover of 3,000 psi unreinforced concrete on top of the Wonder Arch would provide the most suitable aircraft shelter for Southeast Asia.

The USAF construction project ran from July 1968 to January 1970

The Navy construction project started Spring 1969, building 122 shelters in total, at Da Nang, Marble Mountain Air Facility (a.k.a. Da Nang East) and Chu Lai

shelter cost was around $30,000 each

The Checo Report: The Air War In Vietnam 1968 - 1969 reports on page 73:

While 34 aircraft were destroyed in 1968 and 91 had major damage, the figures for 1969 were 6 and 10, respectively

The initial shelter purchase for the Southeast Asia program was the steel arch "Wonder" shelter which had proved successful in tests at Eglin AFB, Fla. Ten of these structures were contracted for and were on their way to Vietnam by 17 February 1968. It was decided to cover these shelters with 12 inches of concrete which would make them sufficiently strong to withstand a 122-mm rocket impact, later changed to a 15-inch cover of 3,000 psi concrete. The program was subsequently expanded to 392 shelters.

Other changes took place during the construction process. The initial shelters were to be 68 feet long, 50 feet wide, and 28 feet high. The length was changed to 70 feet in May 1969 to accommodate a jet blast deflector.

.. the overall cost per shelter remained at approximately $27,000.

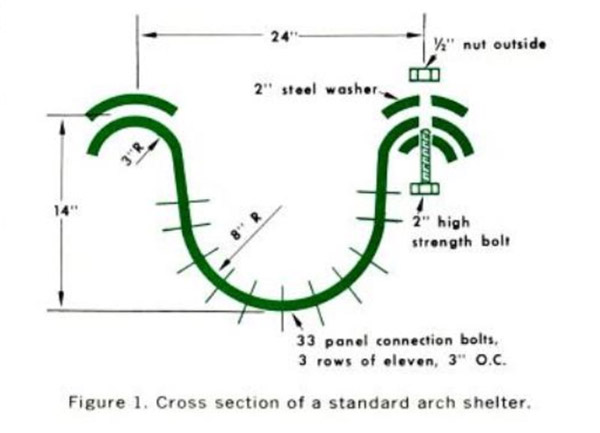

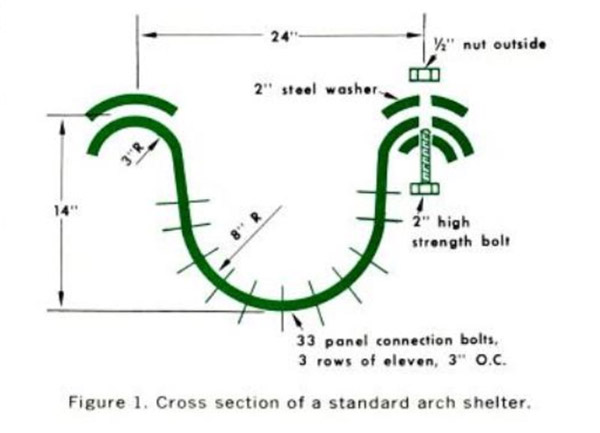

The four-page article Protective aircraft shelter (Air Force Civil Engineer, Volume 10) from May 1969 gives a nice overview of the shelters built in Vietnam. Here's a summary of the technical aspects:

dimensions

fits inside the 52' space of a standard earth-filled steel revetment as used in Vietnam

48' clear span. I read that as the internal space

standard length 72' without front enclosure (as used in Vietnam), 100' with front enclosure

enclosures

front enclosures of steel, aluminum and ballistic nylon [curtains] are being tested

standard rear enclosure is a reinforced concrete backwall with a jet exhaust port

practical Vietnam rear enclosure is the existing revetment, combined with a curved jet blast shield

steel arches

double-corrugated arch elements of 10 gauge (0.1345" / 3.4 mm) steel, 2' wide and 6' to 13' length

arch elements start as a sheet of 46' width, rolled to the shape seen right. Then they are rolled again to create 3' x 1' cross corrugations in the large-radius side, which creates a 24' radius

steel arch elements are bolted together

four steel arch suppliers were found

the steel arch supplier had some trouble producing the specified (thick) gage - new equipment was required

Marwais & Pascoe produced arch elements of ~11' so seven elements were required per arch. Each element weighed 265 lbs.

Young Metal Products produced arch elements of ~8' so nine elements were required per arch. Each element weighed 200 lbs.

covering

covered by either 4' of earth, or 18" of concrete. The latter is poured using steel slipforms

concrete is poured in 4' steps, but with maximum 2' height difference left-right to avoid heavy unsymmetrical loads on the steel arch

appr. 500 cubic yards (382 cubic meters) of concrete is used for a 72' length shelter

end of December 1968, 35 shelters were produced per week

end of 1968, 120 shelters had been erected in Vietnam. Shelter parts were also shipped to Europe and South-Korea

average cost is nearly $200,000

As an addition to the article, I see two different types of concrete covering. Most shelters have a smooth exterior, others have a corrugated exterior. The reason for this difference is unclear.

'Aircraft Shelters in Vietnam' in The Military Engineer gives another overview of the project, and adds that 'Each shelter is composed of 324 panels (with a total weight of 31 tons) bolted together into 36 rings with 15,141 bolts'.

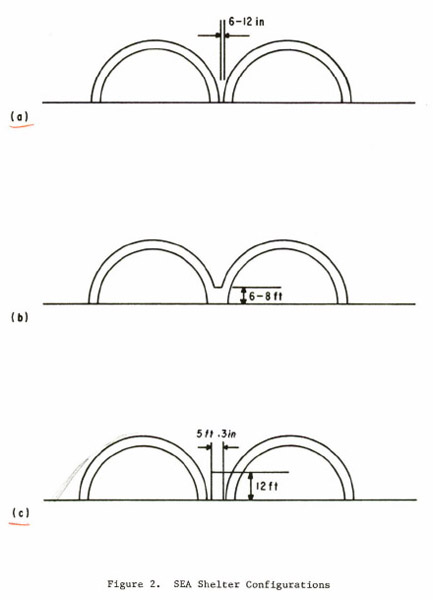

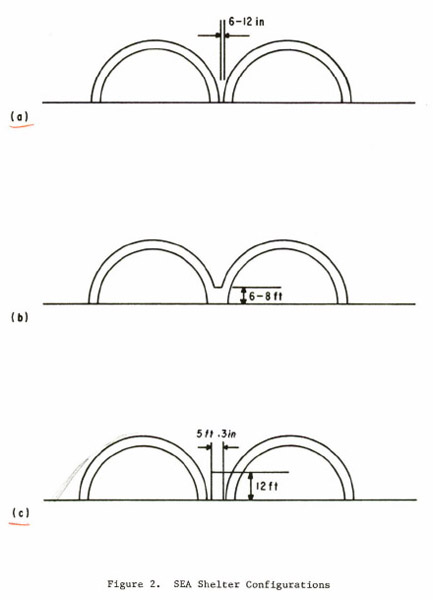

From Aircraft Shelter Explosives Quantity-Distance Evaluation, Concrete Sky, Phase IXB we learn some more details of the spacing between the Vietnam shelters:

adjacent shelters are separated from each other by a 6- to 12-inch air gap

adjacent shelters are connected by a continuous pour of concrete up to a level of 6 to 8 feet

adjacent shelters are separated from each other by a steel bin, earth filled revetment approximately 5 feet 3 inches thick and 12 feet high

The book Engineers at War reports that the US Air Force had planned 408 shelters in Vietnam, at six bases, but 392 were actually built: 98 at Da Nang, 75 at Bien-Hoa, 62 at Tan Son Nut, 40 at Phu Cat, 61 at Phang Rang and 56 at Tuy Hoa.

The book Engineers at War reports on page 452:

unreinforced concrete, fifteen inches thick on ridges and twenty-nine inches thick in valleys

a freestanding backwall gave equal protection and included an opening to let out jet exhaust

a few shelters could also be fitted with a front closure device

sixteen shelters for Phu Cat Air Base were canceled, reducing the number of shelters to 392

page 453 shows a photo of a corrugated concrete mold, explaining the 'ribbed' exterior of some shelters

Navy / Marines 'Wonder arches' in Vietnam, 1969 and on

According to the articles below, Seabees construction engineers built forty-five shelters at Da Nang in 1969, then twenty at Marble Mountain Air Facility (a.k.a. Da Nang East), and finally forty at Chu Lai. They were open at both ends. In Google Earth I count 106 (this includes USAF shelters), 21 and 33 respectively remaining at these airfields. Here are two accounts of the building process, with photos:

The shelter sizes are not mentioned, but they were most likely identical to the 48' USAF shelters. In Google Earth, I measure approximately 51.5' / 15.7 m exterior width, taking the shelters in the north-west corner of Da Nang for the measurements. As far as I could find out, the Air Force used the east side of the base, the Marines the west side.

The USAFE TAB-VEE shelter

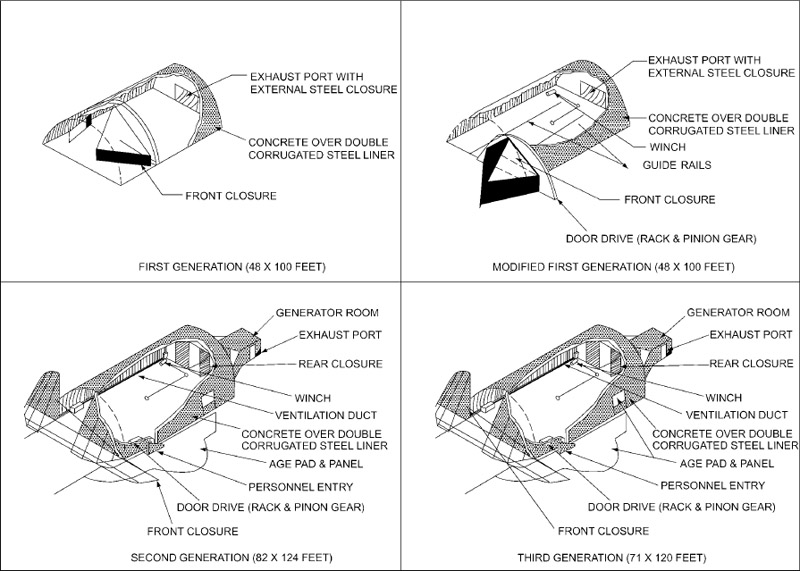

TAB-VEE is short for 'Theater Air Base Vulnerability Evaluation Exercise'. Note that TAB-VEE is also written as 'TAB VEE', 'TAB/VEE', 'TAB-Vee' or 'TAB-V'. This program was started in 1968, following the Arab-Israeli war of 1967, and the Vietnam war experiences. Its aim was to provide better protection for USAFE airfields. It involved better protection for aircraft, runways, ammo storage and other aspects of air bases. Judging from reports online, the design was designed for a conventional bomb to explode near it, but not for a direct hit with one. A submunition or a rocket could be sustained. It could definitely not withstand a nuclear attack. Construction started in 1969, and by April 1972 324 TAB-VEE aircraft shelters had been constructed at Ramstein, Sembach, Bitburg, Spangdahlem, Hahn, Erding, and Zweibrücken (all in Germany), Soesterberg (Netherlands), Aviano (Italy) and Incirlik (Turkey); see Building for peace: United States Army Engineers in Europe, 1945-1991, page 161. The grand total of TAB-VEEs built at USAFE air bases was 396. Note that the TAB-VEEs built in Korea had no doors.

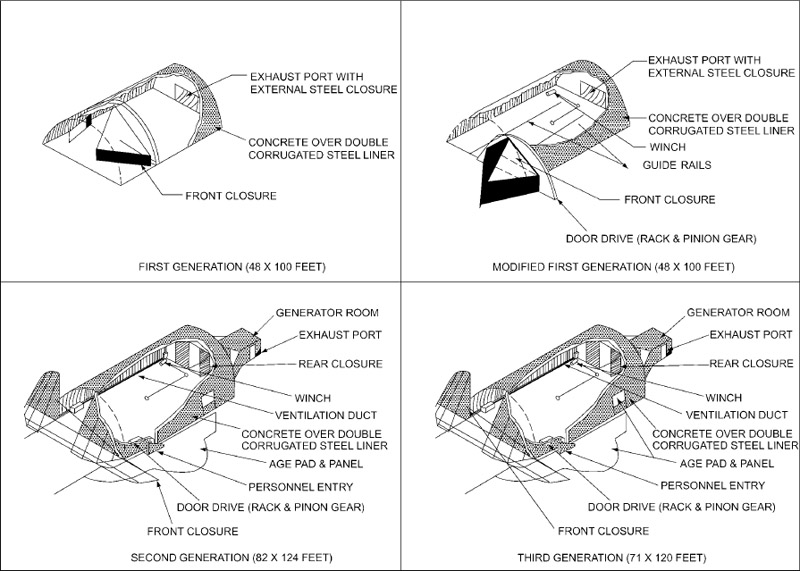

As far as I understand, these first generation shelters were identical to 'Concrete Sky' shelters built in Vietnam, with the addition of a back wall and internal clamshell doors, which required an increased length, from 72' to 100'. The internal length was appr. 90', and the inside width was 48'. However, the clamshell doors reduced the last number to 42' or 43'. The shelter was suitable for all then-current TAC aircraft: F-4E (length 63'0", span 38'5"), F-111 (length 73'6", span swept 32'0") and A-7 (length '", span folded '"), plus any smaller aircraft of course.

During the construction process, it became clear that the F-15, that was under development (length 63'9", span 42'10"), would be an extremely tight fit in span, leaving one inch on either side. I've read that floor rails were fitted to guide the aircraft, but I haven't seen photos that prove this. The height of the double fins (18'8") might also present a problem, but I measure around 1' clearance in a sketch. To solve the problem, a new door was designed, moving the clamshell doors to the front edge of the shelter, where they were welded together and made to slide sideways. This design was built at a few air bases, like Bitburg and Soesterberg (see photo report below, and the shelter census below). These shelters are called 'modified 1st generation' shelters.

Although heavily redacted, Military Construction Appropriations for 1975 give an impression of the era of transition from the TAB-VEE to the next designs.

I think that the F-111 actually required a shelter where it could be parked with the wings swept forward (span 63 ft). Therefore, the introduction of the F-111 in USAFE lead to the 2nd generation shelter, that was probably no longer called TAB-VEE, but Hardened Aircraft Shelter (HAS). Its 124' x 82' internal dimensions more than doubled the floor area. The shelter's cross section has a compound radius, probably by combining arch elements of two radii. The second generation retained the 18-inch concrete roof covering; therefore, the shelter still did not protect against direct bomb hits. The design was not intended to defeat precision attack, nor nuclear attack. The doors were 1' thick concrete, sliding sideways, with a steel spaceframe for stabilization. The original design (not built) had a different recessed door system, consisting of four hinged sections, operating like Dutch doors (as in German shelters). This type was only built at Upper Heyford, 31 pieces, around 1976-1977 I believe. See Air Force Engineering & Services Quartely, November 1977 article.

For reasons I haven't figured out yet, the 2nd generation shelter was very quickly replaced by the somewhat smaller 3rd generation shelter. It shares nearly all design details with the 2nd generation shelter, but internal dimensions are 120' x 71' instead of 124' x 82' (i.e. 84% floor area). It was also easily big enough too for the next type to be added to the USAFE inventory, the A-10 with its 57'6" wingspan and length 53'4". All USAFE shelters constructed after the 2nd generation shelter were of this type. For the fiscal years 1976 to 1978 350 shelters were to be built. Protection levels were the same as before, see High Explosive Testing Of Hardened Aircraft Shelters, with an interesting observation that the inside steel exhaust doors went flying in one test. DoD 'Approved Protective Construction (Version 2.0)' also discusses the same shelter tests.

From: Tech Order 00-25-172 'Ground Servicing Of Aircraft And Static Grounding / Bonding'

From: Tech Order 00-25-172 'Ground Servicing Of Aircraft And Static Grounding / Bonding'

|

| Internal dimensions

| External dimensions

| Features

|

| 1st generation (unmodified)

|

length ~90'

width 48'

door width 42' or 43'

|

length ~100'

width ~53.4'

|

Clamshell doors inside the shelter

Personnel entrance through door in left-side clamshell door

Patch on the exterior

I think different types of exhaust deflectors were used, maybe even on one air base.

|

| 1st generation (modified)

|

length ~100'

width 48'

|

length ~100'

width ~53.4'

| Single sliding door, made from clamshell doors

Personnel entrance through sliding front door, left side

No patch on the exterior

I think different types of exhaust deflectors were used, maybe even on one air base.

|

| 2nd generation

|

length 124'

width 82'

|

length '

width ~88' = 27 m

|

Personnel door on the right side

Inverted J type ventilation tubes on top of shelter, usually alternating left and right

Concrete apron for ground equipment on the right side, with possibly a lead-through in the shelter wall

|

| 3rd generation

|

length 120'

width 71'

|

length '

width ~77' = 23.5 m

|

Personnel door on the right side

Inverted J type ventilation tubes on top of shelter, usually alternating left and right

Upward-pointing 'wings' on the exhaust deflector

Concrete apron for ground equipment on the right side, with possibly a lead-through in the shelter wall

However, ground equipment is often seen inside the shelter too

|

I found some photo reports showing USAFE TAB-VEE shelters:

Google Earth also has lots of excellent photos of shelters made on air bases that are no longer in militrary use.

USAFE shelter census

I used Google Earth, including its historical imagery, to do a rough count of shelters on USAFE air bases. Air bases indicated # are deployment air bases, only used in exercises. Air bases indicated % are A-10 Forward Operating Locations, used irregularly by 81TFW.

NOT YET COMPLETE!

|

| 1st generation

unmodified

| 1st generation

modified

| 2nd generation

| 3rd generation

| Comments

|

| Ahlhorn %

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 17

|

|

| Alconbury

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 26

| Additionally 13 super-wide shelters for TR-1 / U-2R

|

| Aviano

|

|

| 0

|

|

|

| Bentwaters

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 21

|

|

| Bitburg

|

|

| 0

|

|

|

| Boscombe Down #

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 18

|

|

| Erding #

| 18 *

| 0

| 0

| 0

|

* one 150' version.

This is probably the most undisturbed set of first generation shelters

|

| Gilze-Rijen #

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 16

| constructed in 1976 and 1977

|

| Hahn

| 43

* **

*** ****

| 0

| 0

| 2 *****

|

* I count 18 in the south shelter area and 25 north shelter area

** one more in the north-west of the north shelter area, not connected to taxiway

*** one 150' version in each shelter area

**** five demolished in the south shelter area

***** one each in both shelter areas, but the one in the south area was demolished

|

| Incirlik

|

|

| 0

|

|

|

| Jever #

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 23

| constructed in 1976 and 1977

|

| Lakenheath

| 0

| 0

| 0

|

|

|

| Leipheim %

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 10

|

|

| Norvenich %

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 10?

| 3 remaining

|

| Ramstein

|

| 0

| 0

|

| * in the east shelter area, ~ seven 1st gen shelters closest to the taxiway-turned-runway were demolished between 2000 and 2010

** in the west shelter area, the two 3rd gen shelters closest to the taxiway-turned-runway were demolished between 2000 and 2010

|

| Sembach

| 0

| 0

| 0

|

|

|

| Soesterberg

| 0

| 18 *

| 0

| 17 ** ***

| * 5 remain, rest demolished. One 150' version. Area not open for public.

** area open for public, some shelters are open

*** constructed in 1977

|

| Spangdahlem

| 48 *

| 0

| 0

| 24

| * including two 150' versions

|

| Upper Heyford

| 0

| 0

| 31

| 27 *

| * 9 north side, 18 south side

|

| Woodbridge

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 17

|

|

| Zweibrücken

| ~41 *

| 0

| 0

| 0

| * 10 of ~23 remain in the north shelter area, all 18 in the south shelter area are demolished

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total

| 150

| 18

| 31

| 228

| Grand total 427 so far. RAND reports: 'By the end of the Cold War, the United States had constructed roughly 1,000 such shelters in Europe and the Pacific'.

|

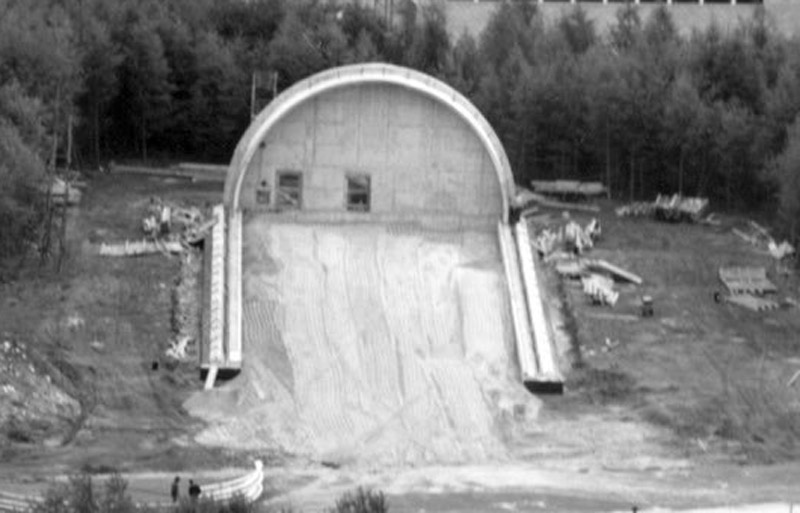

Soesterberg TAB-VEE shelter construction, 1969

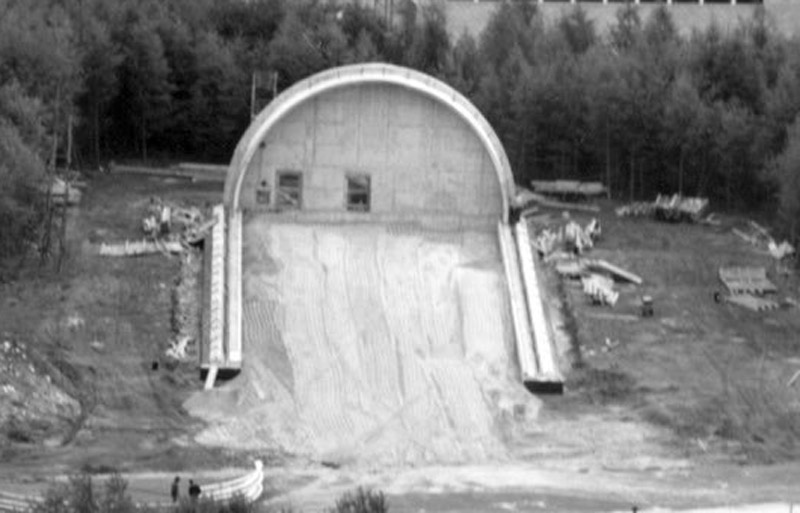

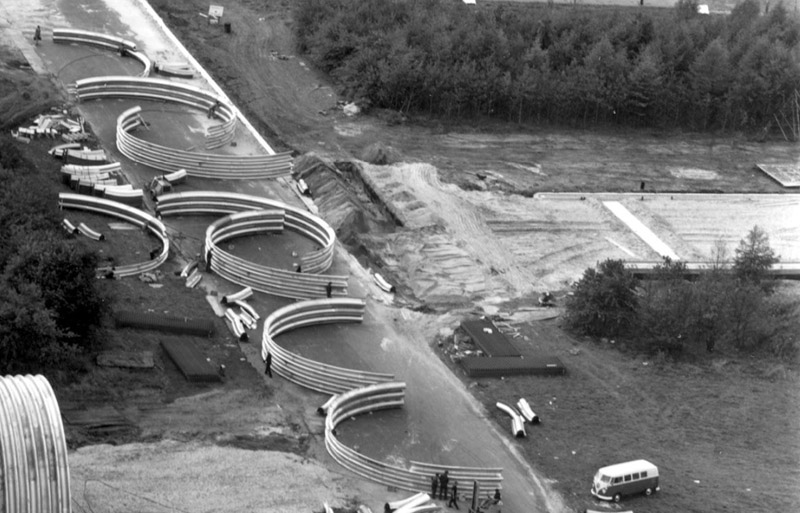

The Royal Netherlands Air Force took great aerial photos during the construction of first generation (modified) TAB-VEE shelters at Soesterberg in 1969. I found the photos on the website of the Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie.

| Start of construction of the foundation. Lots of rebar. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

| Concrete edge foundation is cast, but no floor is laid yet. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

|

| Casting of the rear wall. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

| Rear wall with a 'lip' to connect with the Wonder arches. This rear wall has unusual exhaust gas openings. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

|

| Some shelters were built with the shelter floor and ramp constructed first. The foundations for the two shelters themselves are also visible. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

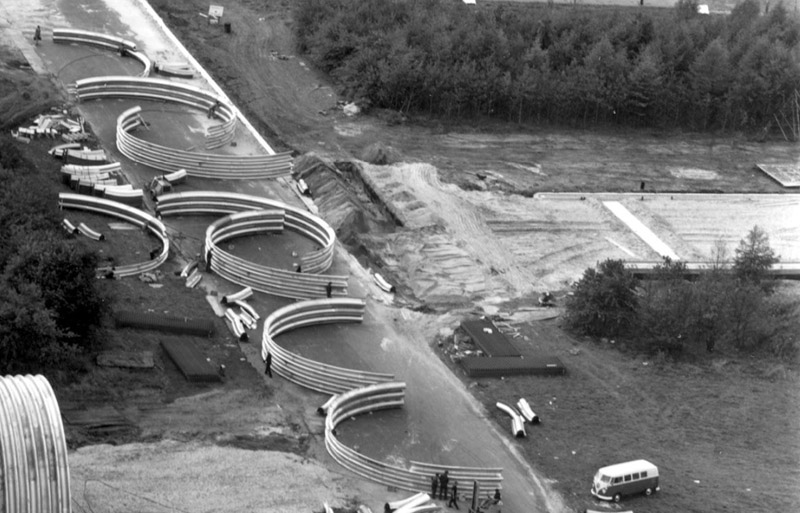

A taxiway is used to assemble the Wonder arches. First, the Wonder arch elements are bolted together to a single span, then more elements are added until three rows of elements a are bolted together.

Since the combined weight of a three-row arch is probably around 5500 lbs / 2500 kg, a crane is most likely used to move the arches to the shelter site. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

|

| The first three-ring Wonder arch is positioned against the back wall. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

| The Wonder roof has been built up here, against the concrete back wall, that still lacks the exhaust channel. It's not clear what the workmen are doing here, possibly tightening all the bolts? There is no rebar visible on the Wonder roof, but there is rebar for the future exhaust. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

|

| Another photo of the same stage. The standard exhaust opening in the rear wall is clearly visible here. It's about the size of the VW bus. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

| The outer casing for the concrete pouring is being assembled here. A crane is on its way with the one but last casing element. The casing elements connect to the small dark rectangles on the foundation. On the top side, they connect to the opposing element with a framework. Note that the casings leave the very top of the shelter open; it seems that area is flat enough for concrete to be shaped by hand. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

|

| The same situation from a different angle. There is no casing yet to close the semi-circular slot on the front side of the shelter. We can see that there is no concrete floor in this shelter yet. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

| It looks like the concrete has been poured on this shelter. Again it seems to lack a concrete floor. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

|

| In this photo the exhaust channel has been added, blowing upwards. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

In this photo, construction of the ramp that connects the shelter with the taxiway is underway. I think I see leveled and compacted sand with vertical wooden (?) planks, ready for pouring concrete. Again, no rebar is in sight.

On the shelter itself, the edges of the pouring casings can be seen, they leave two ridges on the top of the shelter. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

|

| The shelters were fitted with a single sliding door, that is being sandblasted or painted here. As far as I can tell, the strange shape of the door is explained by its former intended use as two swinging doors mounted inside the shelter. For the doors to opening inside a semi-circle, they required this unique shape. The two doors of the original design were simply welded together.

While closing, the door slides in a quarter-circle channel on the left side of the shelter. This probably also explains the small step in the circumference of the door. Interestingly, none of the photos show a guide rail on the ramp, possibly this was an afterthought?

Also, the concrete looks very weathered already. Just maybe the doors were fitted some time later? Two ramp lights have also been fitted to the shelter. Photo courtesy of NIMH.

|

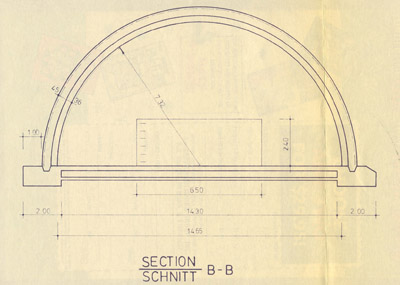

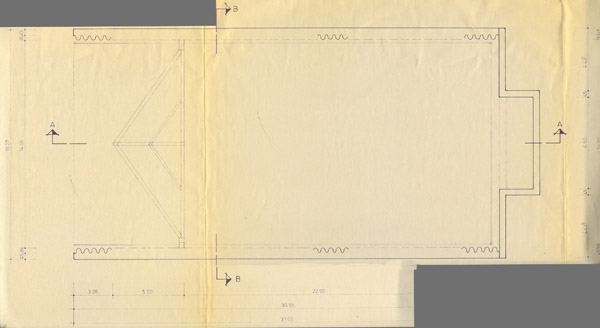

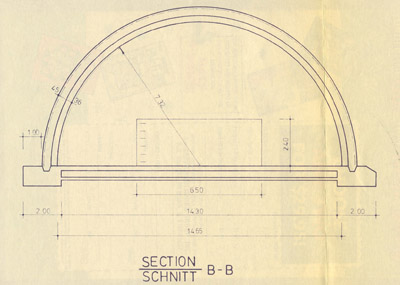

Zweibrücken construction drawings

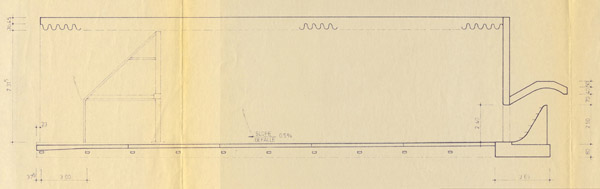

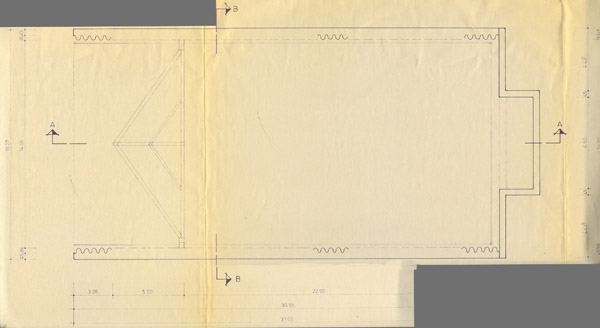

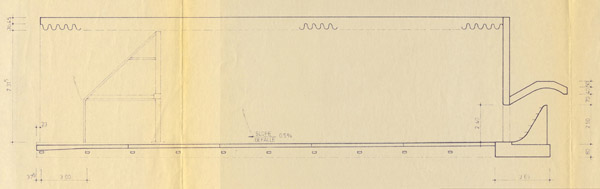

Larry Engesath very kindly sent scans of basic construction drawings, that he saved from his years at Zweibrücken as a camera technician. They clearly show the original 1st generation type, unmodified, with the doors inside the semicircular shelter. Measurements are in SI units.

Exterior details

Just started, more to be added

thicker patch seen on many, 25% from front, roughly 2 x 2 meters, maybe detail of the door installation (Erding, Hahn)

paint, camouflage. Ramstein, Incirlik, Hahn has some color differences.

-

Interior details

Just started, more to be added

based on the Vietnam shelter, I calculate that 51 arch rings were used in a TAB-VEE shelter. But a count of a Soesterberg photo shows 50 rings. That makes more sense too, since 50 x 2' makes a 100' shelter, plus a little bit.

based on the Vietnam shelter, we know that each ring was bolted together from 9 arch elements. The connections were distributed somewhat. I still have not found out whether all arch element overlaps were in the same direction, or alternating, of switching in the middle.

water leaking through the joints of the arch elements creates interesting patterns on the interior.

an area roughly 1x1 meters of the arch structure is cut out, to make room for the upper hinge of the clamshell doors. This probably relates to the 'patch' mentioned above. And just maybe this is the result of a design change to enlarge the door opening from 42' to 43', in an attempt to make the unmodified 1st generation suitable for the F-15

ventilation problems, running aircraft

door stops

x

Other countries

The air forces of many other countries built the same type of shelters. So far I've identified Greece, Italy, Spain and Iran. As far as I can see, they all built the 1st generation TAB-VEE shelter. Maybe the size was slightly different, for example at Villafranca I measured ~18 m width, instead of ~16.3 m for the USAF TAB-VEE.

Maybe also used by RAF as standard? 1st gen RAFG had a very different design.

Dunn, Base Development, p. 65;

https://books.google.nl/books?id=OuALAAAAIAAJ&lpg=PA18&ots=v7s23S1WKn&dq=Dunn%2C%20Base%20Development&pg=PP9#v=onepage&q=Dunn,%20Base%20Development&f=false

Tregaskis, Southeast Asia: Building the Bases, pp. 388-90;

https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/seabee/explore/online-reading-room/Publications.html

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=Fox%2C+Air+Base+Defense+in+the+Republic+of+Vietnam

Fox, Air Base Defense in the Republic of Vietnam, pp. 70-71,

https://www.flugzeugforum.de/threads/shelter-f-4f-phantom-1-144-michi-s-modelmania-spezial.30230/

Return to models page

From: Tech Order 00-25-172 'Ground Servicing Of Aircraft And Static Grounding / Bonding'

From: Tech Order 00-25-172 'Ground Servicing Of Aircraft And Static Grounding / Bonding'